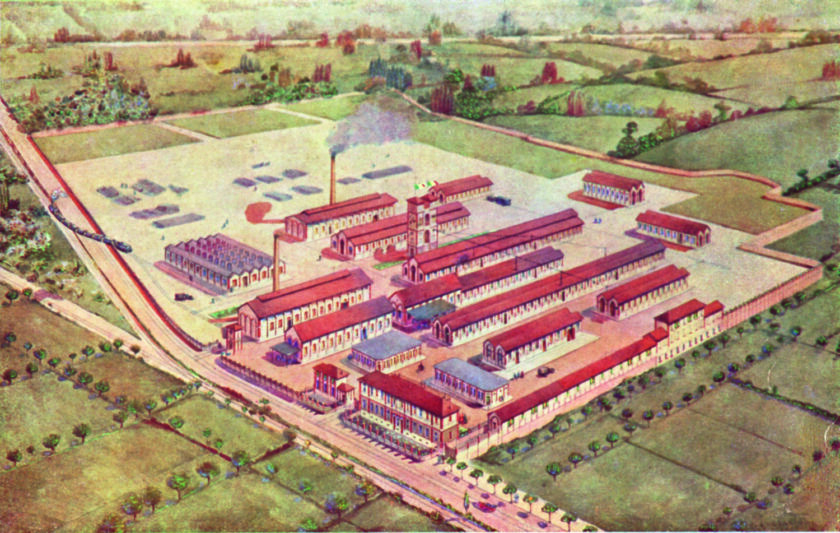

In 1880, Giulio Gianetti, a merchant in iron and steel profiles and hardware, founded the “Società Anonima Giulio Gianetti” in Saronno, in the province of Varese but near Milan. The company aimed to produce rims and axles for carts and carriages. Over time, it became one of the most established manufacturers of iron rims, which were applied to wooden wheels at the time. The success of production in 1913 led Gianetti to open a new plant in Ceriano Laghetto, a location near Saronno, to accommodate various types of processing necessary to produce not only rims and axles but also metal parts for furnaces, agricultural and construction machinery, and motorcycles. The new factory, of considerable size and served by a railway, housed a foundry for cast iron, steel, and other metals, had machines for forging and stamping, and could also carry out electric and acetylene welding. A specific department also performed wire drawing of iron wire and its derivatives, all activities that, however, with the end of the First World War and the exponential growth in demand for agricultural machinery, ended up being supplemented by the production of manual-drive motor cultivators, self-propelled motor cultivators, harrows, mowers, and hay rakes.

The “Ditta Giulio Gianetti di Giuseppe e Gaetano Gianetti” thus ended up entering the agricultural mechanization sector, to the extent that by 1920 it offered a wide range of agricultural equipment which, however, within a few years, were abandoned in favor of the main activity based on the production of wheels, axles, and their accessories as well as mechanical components. These products were distributed globally and supplied clients such as Iveco, Daimler, Volvo, Harley Davidson, and others. Nevertheless, the company remained a family-run business that had to deal with increasingly structured competition, and for this reason, at the beginning of this century and after already abandoning agricultural production, the ownership decided to sell the majority of shares to the Accuride Corporation group, a global giant in commercial vehicle components with its headquarters in Indiana and about ten plants scattered across the United States.

This allowed the company, now renamed “Giannetti Wheels,” to grow, but in August 2018, it was absorbed by the German Quantum Capital Partners through its Quantum Opportunity Fund II, which in May 2019 also acquired the steel rim manufacturer “Gkn Wheels Carpenedolo.” Thus, the “Gianetti Fad Wheels” group was born, with a production capacity of over two million pieces per year through the two plants in Carpenedolo, near Brescia, and Ceriano Laghetto, with the latter being closed in July 2021 by the German financial company following the decision to decentralize production abroad.

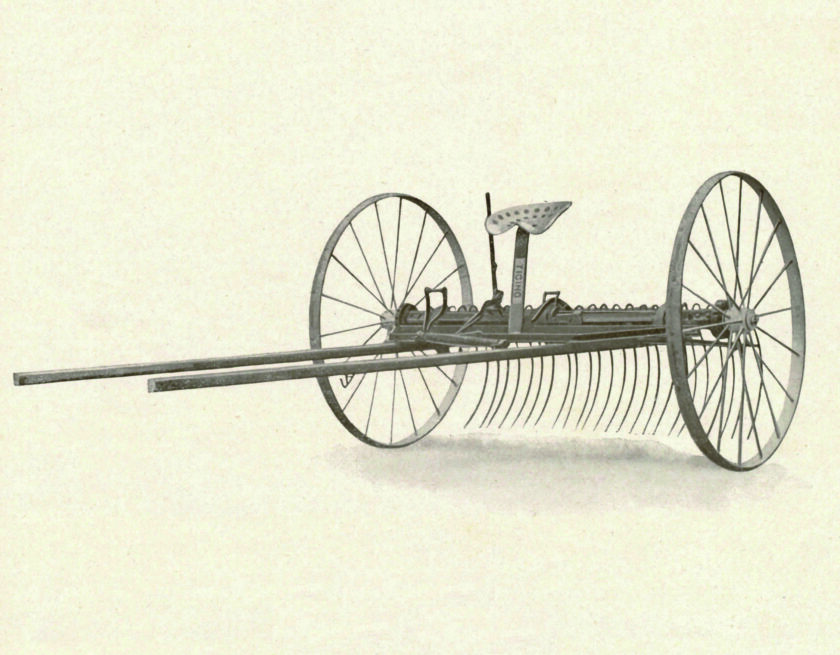

The “Ticino” rake

One of the simplest agricultural machines offered by Gianetti was the “Ticino” hay rake, designed to be pulled by a horse and therefore lightweight and robust. It was supported by two large metal wheels composed of a cast iron hub carrying an interchangeable cast iron compass on which iron rims with curved bands were fixed by electrically welded spokes. Very sturdy and able to withstand impacts with plants or walls without damage. The wheels supported an iron angle crosspiece that housed at the ends two discs for the pedal shafts and the two wheel hubs, which were removable for repairs or replacements. The rake tines, 24, 30, or 36 depending on the customer’s needs, were made of high-quality round and elastic steel. They were fixed with stamped steel supports to facilitate disassembly and replacement, while a perforated seat with leaf spring accommodated the driver who, through the pedals or a lever, raised the rake tines when necessary.

The “Adda” mower

Mechanically more complex than the “Ticino” rake was the “Adda” mower, a tool that was driven by its own wheels. It was designed to be operated by animal traction and featured a long wooden shaft with two balance beams. The operator, seated on a perforated metal seat, could engage or disengage the lateral cutting bar via a lever, and if the horses pulled back, a system of notches applied to the wheel hubs made these groups idle, thereby isolating the bar. To transfer power from the wheels to the bar, Gianetti exploited its mechanical and metallurgical expertise, creating a sealed box containing tempered steel gears with milled teeth that worked immersed in grease. The cutting bar consisted of a rolled steel crossbar with stamped steel teeth and tempered and sharpened blades and counter blades, and all components were easily removable. The lifting of the bar occurred in two distinct phases, the first of which, up to 20 centimeters in height, allowed cutting at various heights as the bar remained parallel to the ground. Above 20 centimeters, the bar began to fold vertically, and automatic disengagement of the movement occurred thanks to a safety stop.

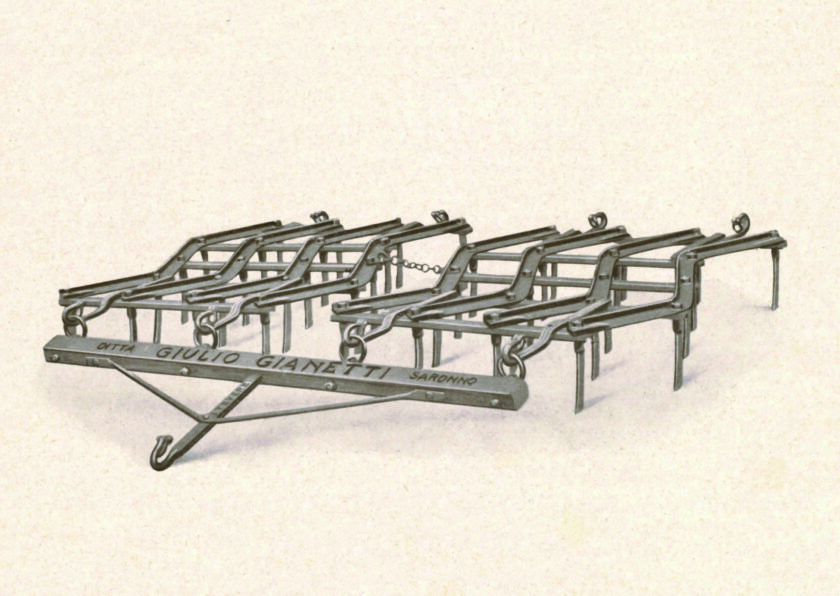

The “Tevere” harrow

Another simple yet very robust implement made by Gianetti was the “Tevere” harrow, which could be pulled by animals or the rare tractors in operation at the time. Several types were offered, coded with numbers 1-2-3-4 or 5 corresponding to the number of sections that made up the harrow. The distance between the teeth could vary from 35, 40, or 50 millimeters depending on the type of work to be done, and the frames were built from L or U-shaped iron frames whose elastic and rigid characteristics changed depending on the work for which the harrow was intended. The stamped steel teeth were fixed to the crosspieces with a system that prevented rotation but were always removable and interchangeable.

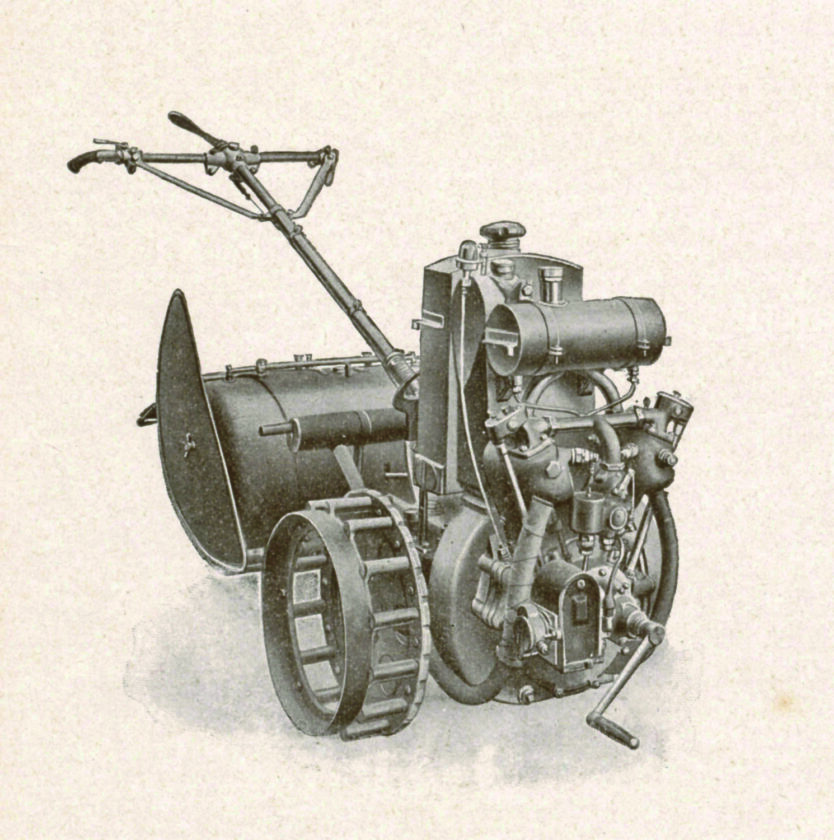

The “Type 5 and 8 HP” motor cultivators

The flagship of Gianetti’s “agricultural” production was the motor cultivators, produced in different models with manual or self-propelled drives, that is, with a driver’s seat. The manual-drive models were two, “Type 5 HP” and “Type 8 HP” due to the different power of the two-cylinder V-shaped petrol engines that propelled them. Common to both engines was water cooling with a radiator and crank ignition controlled by a high-tension magnet, and they also shared a belt transmission that connected the engines to a two-speed gearbox. A cardan shaft also transmitted power to the rear implement, a rotary cultivator consisting of a rotating hollow shaft with springs on which were attached tine cultivators in the shape of small hoes. The tines were replaceable, and the springs could move laterally in case of impact with resistant objects such as stones or roots. The vehicle was driven standing up, thanks to a tiller with a handlebar with two grips, on which all the controls of the motor cultivator were located. It was very maneuverable and could turn around on itself. The cultivator had a working width of 55 to 85 centimeters, and the cultivation depth, depending on the forward speed and the nature of the soil, ranged from 10 to 25 centimeters.

The “Type 20 and 30 HP” motor cultivators

The top-of-the-line machines in Gianetti’s production were “mini-tractors” with three wheels powered by four-cylinder petrol engines delivering 22 or 32 horsepower at one thousand revolutions per minute. They were water-cooled with a radiator and pump, ignition was by crank with a magnet, and a regulator controlled fuel input. The vehicle’s structure was a load-bearing frame on which the engine, transmission, driver’s seat, and rear tiller were placed, and the gearbox had three forward gears and one reverse. The driver’s seat, quite comfortable, featured a small, almost vertical steering wheel that operated the central front steering wheel. Since it was not visible to the driver, a small indicator placed on the front linkage indicated its position, straight or turned. It could rotate almost 90 degrees, providing the vehicle with excellent maneuverability. The cultivator’s working width was one and a half meters with a depth of 25 centimeters, and with minor modifications, the vehicles could also operate a mower or a reaper.

Title: Gianetti agricultural tools and motor cultivators, when agriculture is history

Author: Massimo Misley